In the last article we talked about how and when to use an

effective crossover run.

Here, we’re going to slow down a bit, literally, and talk

about a movement that every performance coach (and most athletic coaches) teach

on some level: The shuffle.

Most coaches understand that a shuffle is simply a lateral

movement where we don’t cross our feet.

Just like with the crossover run, it’s important to

understand why and when an athlete should use a shuffle in the first place.

While the crossover is used when we need to move as fast as

possible while keeping square with an opponent, or tracking a ball, the shuffle

is generally used in small spaces where we’re able to keep the opponent in

front of us without crossing our feet.

This is as fast as I can move at 9:30pm at 34 years old. Notice the feet coming together (they don't have to click, but it's not the worst thing if they do). The key question as a coach, before you step in to change something: "Is that as fast as this athlete can possibly move right now?" If the answer is "yes" or even "probably", then they just need time, repetition and strength.

The advantage here is the ability to change directions

really quickly – our lateral orientation stays intact. The disadvantage is it

is slower than either a crossover or a straight ahead sprint.

Athletes that compete aggressively on defense (or without

looking over their shoulder at a coach or parent) generally learn to transition

from a shuffle to a crossover or sprint when needed. In other words, they use a

shuffle whenever possible until it can’t get the job done on a given play.

Think man-to-man defense in basketball.

Their only focus should

be on doing whatever it takes to keep the opponent in front.

Now that we have an understanding of the when and why, let’s

take a look at the how.

There’s a couple of mistakes we see made when teaching or

coaching this movement that I’m going to try to clarify and simplify here.

COACHING MISTAKE #1:

COACHING TO AVOID FEET “CLICKING”

First, we hear coaches consistently tell their players to

avoid letting their feet come together. Their hearts are in the right place –

the assumption is that allowing the feet to meet underneath the pelvis might

make the athlete trip over their own feet. I can speak from experience as an

athlete (and a clumsy one at that), along with countless coaching sessions

working on this movement and confidently say that this is not the case – you will almost never see an athlete fall over from

this.

The next question should be “so what?” What’s the advantage

of not restricting the feet?

It should help to think of the shuffle as a gait cycle (Lee

Taft specifically coined the term “Lateral Gait Cycle”). Just like in

sprinting, each leg has an entire cycle to work through to produce the maximum amount

of force with each push. With the shuffle, it’s an alternating push-pull cycle.

The lead leg (i.e. left leg when moving to the left) is the “pull” leg. The

back leg (right leg when moving left) is the “push” leg.

[Slow Mo Video]

A full cycle for the lead leg means a big reach out to the

side in the direction of travel (with the toe turned out), the heel digs into

the ground and begins to pull. The full phase is finished once that foot is

underneath the pelvis or center of mass.

While that is happening with the lead leg we see the back

leg go through an entire push cycle. We’ll start with the finish: “Toe off”

with this leg coincides with heel contact on the front leg. While the front leg

pulls, the push leg gathers and prepares for the next push by moving underneath

the center of mass. This will happen as the front leg finishes its pull (also

under the center of mass). This is where the feet meet in the middle.

In some athletes, but not all, this means the feet will

actually hit in the middle when attempting to shuffle at full-speed. My

suggestion is to let this happen and focus on something else that may need

cleaning up. By trying to take away the feet meeting in the middle, you would

essentially be asking the athlete to use less power on each leg. The push-pull

cycle would be incomplete and they’d gain less distance with each stride. In

other words, they’re toast.

COACHING MISTAKE #2:

COACHING TO AVOID TURNING LEAD TOE OUT

I briefly mentioned above that the toe on the lead leg will

turn out during the pull cycle. The second most common mistake we see many

coaches make is putting it in the head of the athlete that their lead toe

should never turn out.

But why?

The rationale seems valid on the surface. Most speed &

agility coaches will turn to deceleration and say “we need the ankle

dorsiflexed (toe straight ahead) in order to cut properly, so it’s more

efficient to shuffle with it already straight ahead”.

You may remember from the crossover article why we let the

toe turn out at the start (called the directional step) and the analogy of

trying intentionally to run an 8 cylinder car on only 4 cylinders just to

improve stopping ability.

That’s great, unless you’re in a quarter mile race and need

every last bit of power you can muster.

In the situations in sport where we’d need to use a shuffle

at full speed we know it’s faster to

shuffle with the toe out. And the great thing is we don’t have to coach it as

long as the athlete is focused on the right thing – competing and not letting

an opponent by!

The next great thing is we usually don’t have to teach the

athlete what to do with the foot when they do

have to stop and change directions. It’s another one of the innate abilities we

have to figure out the best position possible for a given situation – part of

our fight or flight response – if the athlete can get into a fight-or-flight

mentality while competing.

An obvious exception here would be any physical restriction

that keeps them from getting into dorsiflexion.

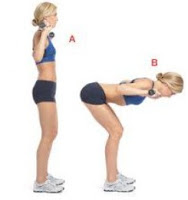

Toe turns out, hips stay mostly on the same level. Focus is on pushing the ground away and being fast!

SO WHAT CAN WE COACH?

We’ve focused mostly on points of shuffling that we shouldn’t

step in and correct, but where does that leave us as coaches?

Don’t worry, there’s plenty for us to do when it comes to

developing lateral speed!

ATHLETIC POSITION

Athletic position is something that’s talked about often but I don’t want to

downplay it here. Having an athlete that understands what a good athletic

position looks, and more importantly, feels

like is a great way to start working on a strong shuffle. Spend time getting an

athlete to know the difference between a defensive

athletic stance and a more traditional one.

A defensive

stance will typically have a much wider base than your run-of-the-mill shoulder

width stance that most will refer to. Why? Better to push laterally!

GET IN THE TUNNEL, STAY IN THE TUNNEL

Once the athlete

is in a good athletic stance, we like to cue them to imagine being in a short

tunnel. The goal with the athletic position, along with the shuffle itself, is

to avoid hitting your head on the top of the tunnel. This is a good visual to

keep their elevation consistent and make sure no energy is lost through the

body moving up and down during a drill or competition.

With

younger, weaker athletes (especially if they’ve gone through a recent growth

spurt) you’ll see a little bit of struggle with this, but that’s OK…stay

patient, encourage and make sure they want to come back. Eventually they’ll get

it!

BIG POWERFUL SHUFFLES!

Many coaches

will teach athletes to take short, quick shuffles where their feet move fast

but they don’t really go anywhere. This can also be a byproduct of having them

avoid clicking their feet together.

What we

really want to see is an athlete that is so aggressive they gain maximum ground

with each shuffle without overreaching and changing their elevation. A fun

demonstration is to take two athletes of very different speeds and make them

race using a shuffle for 8-10 yards. The athlete who is clearly faster is told

to take short quick shuffles and to not let

their feet come together. The other athlete is simply told that their focus is

to win! I’m sure by now you can guess

where this is going.

SUMMARY

To wrap up, we need to look at shuffling and all lateral

movement from a “whole-part” vantage point rather than a “part-whole”. In other

words, instead of trying to deconstruct the movement and piece it together

one-by-one with each athlete based on what we’ve read or heard, try to observe

great athletes move in competition.

Sometimes our instinct as performance coaches is to

immediately find things for us to “fix” but I’m a firm believer that

understanding the natural ability humans have to be fast in a fight-or-flight

environment will teach us more about how to coach speed than we ever could by

trying to teach from an anatomical & biomechanical standpoint.

One cool

thing is when we take this “whole-part” approach, the anatomy and biomechanics

make complete sense within that framework, but if we try to put an anatomical

solution to movement first, it’s easy to misinterpret what is actually going

on.